Ten years and a few thousand elbow patients ago, I designed a strengthening program to help climbers recover from tendinosis. The regime was outlined in “Dodgy Elbows” [Rock and Ice, No. 156]. It’s the most downloaded article on rockandice.com, which speaks volumes for how common elbow pain is among climbers.

You may be surprised to learn that tendinosis is not the same as tendonitis! The former is a chronic degenerative condition, while the latter is characterized by acute inflammation. That tendonitis is used as a blanket term, even by many medicos, to describe any discomfort within vague proximity to the elbow belies the fact that the vast majority of elbow pain relates to tendinosis.

I can’t remember the last time a patient presented with actual tendonitis because most people will intuitively rest before making an appointment, during which time it settles down. Tendinosis, on the other hand, will not yield to rest. Try it and the pain may subside (or not), only to rear its ugly nubbin as soon as you resume climbing. The fundamental premise of eccentric loading, which I detailed in the original program, is unchanged, but over the years I have refined how the program breaks down in terms of load, angles, repetitions, sets and frequency. Other adjunctive therapies that I used to recommend, such as icing, have been dropped altogether.

CAUSES

When you climb you increase your muscles’ physical requirements and the associated structures must adapt. Muscles such as the biceps, triceps and those in your forearms can get stronger considerably faster than the tendons that anchor them to the bone.

The catalyst for generating this strength differential and subsequent injury is typically a change of habit. Ramping up your training program, for instance, or suddenly increasing the volume of climbing will cause your muscles to strengthen rapidly, often outstripping gains in tendon strength. Although the tendon is unlikely to break, it is likely to degrade, causing cellular changes that result in tendinosis.

There is no wizardry that will make tendinosis go away. You strengthened yourself into this predicament, and you need to strengthen yourself out of it.

SYMPTOMS

Pain is the catalyst for most people to become concerned. The pattern of the pain, however, is what differentiates tendinosis from other tendon conditions such as tendonitis or a tendon tear. If your elbow has a burning pain around either epicondyle for up to a week following an aggravating activity, you probably have tendonitis.

At three weeks, that tendonitis is rapidly morphing into tendinosis. Though most tendon conditions in the elbow will cause pain around either epicondyle, there is usually more bone sensitivity right on the epicondyle with tendinosis. A good test is to tap the boney lump with a knuckle. The test is positive if you curse. Pain that is worst when you are warming up and virtually disappears during your session, but then returns after cooling down, is classic tendinosis. Pain that increases or does not subside is likely a tear in the tendon, tendonitis, or some other condition or injury.

LOCATE

When loaded, cells affected by tendinosis elicit pain (unless you have warmed up). A healthy aversion to pain has its place, but in this instance pain is your radar for locating problem cells—avoid pain and your therapy will be ineffective.

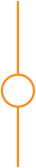

Most cases of tendinosis occur in either the common flexor tendon, which attaches to the medial epicondyle, or the common extensor tendon as it joins the lateral epicondyle. Each of these common tendons is fanshaped, and hence loaded quite differently by muscles that attach to it. If the elbow angle changes, the loading pattern will change, too. Ninety-five percent of medial epicondylosis cases involve flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) and/or pronator teres (PT). Lateral epicondylosis typically involves the wrist extensor on the thumb side called extensor carpi radialis longus. Although each version requires a different exercise, the remainder of the protocol is much the same.

TESTING PROTOCOL

To target the affected tissue, you first need to locate it. The muscles listed above all cross the elbow to anchor on their respective epicondyles on the humerus, so getting the elbow angle just right during the curative exercises is paramount.

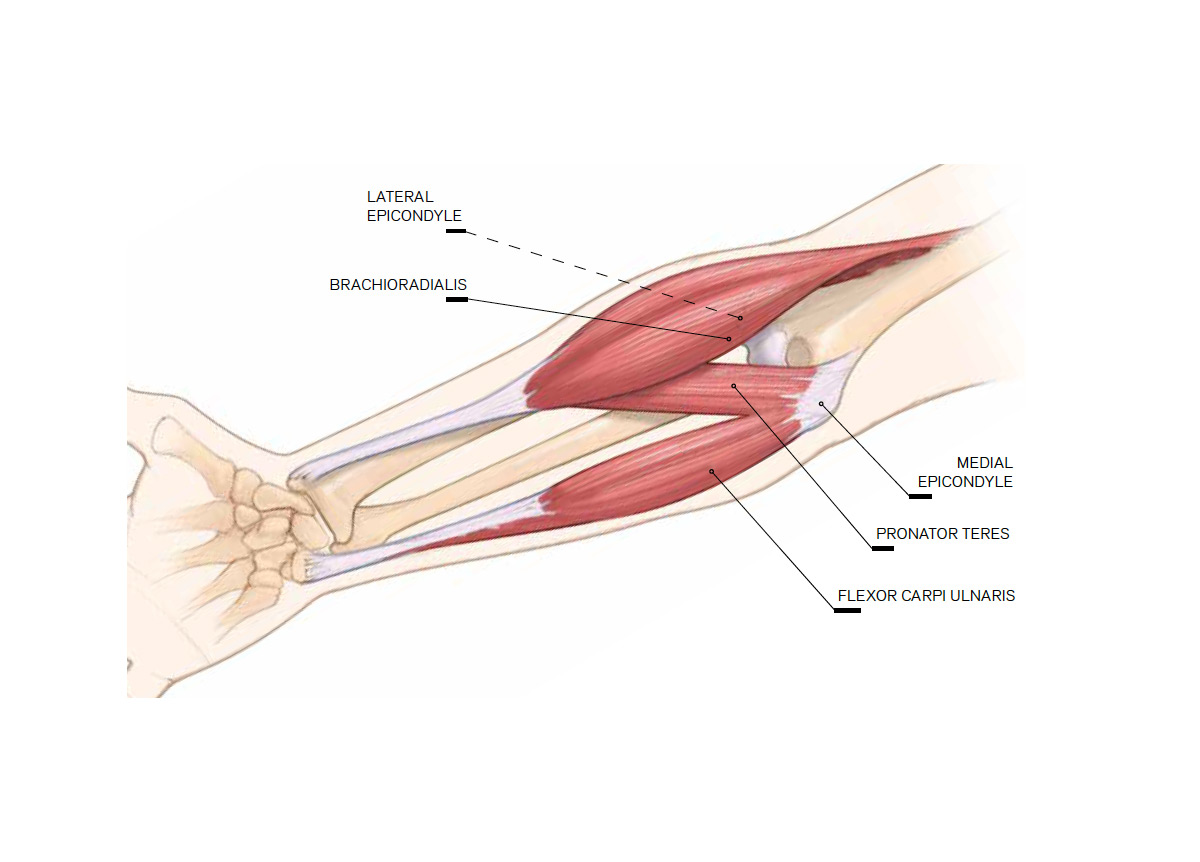

To test your medial epicondylosis, you will need to test both the FCU and PT. You may need to do one or both exercises depending on whether they are painful during testing. For FCU, load a dumbbell with 12 to 20 pounds depending on your strength. Distribute the weight two-thirds on one side and a third on the other. Note that your thumb in all exercises grips the bar on the same side as your fingers.

When the dumbbell is in your hand, the heavier end should be on the little-finger side. Place your arm (palm up) across a table top with about half of your forearm over the edge (Figure 1). Lean to the side, over your arm, such that the medial epicondyle rises an extra inch or so above the table surface. With your elbow fully extended (0 degrees of flexion), lift the weight with your other hand (don’t weight the arm you are testing just yet) so that your wrist is in full flexion (Figure 2). Slowly lower the dumbbell until the wrist is fully extended (Figure 3). Lowering the weight for this and all repetitions for all tests and exercises should take five to seven seconds. There is no need to roll the bar down your fingers while you release your grip, as the FCU is a wrist flexor only. Repeat this process at 45 degrees (Figure 4), 90 degrees (Figure 5) and 135 degrees of elbow flexion (Figure 6). Go back to the position where you felt the most discomfort, then refine the angle to receive your diploma in Masochistic Tendencies. Eighty percent of people will have maximum pain somewhere between the first two testing positions, and most of the rest of you sufferers will yelp at close to full flexion.

Follow the same basic setup for pronator teres (PT) but don’t tilt your arm. Place four to six pounds on one end of the dumbbell. To get the correct amount of load (such that it feels like depleted-uranium bullets are being shot into your elbow), simply move your hand on the bar to create more or less leverage. Place your arm along a table surface with the elbow extended (Figure 7). Hold the dumbbell in a vertical position with the weighted end on top. Lower the weight slowly to the outside until it is horizontal (Figure 8), not further, and then assist the weight back to the starting position with your other hand. Test each angle.

Testing lateral epicondylosis can be a little tricky. Place weight on one end of the bar or use something similarly disproportionate— say, a cast-iron skillet. This weight will be on the thumb side. Place the inside surface of your arm (the non-tanned side) flat against a table top with your elbow fully extended. Your armpit will be against the edge or level with the table surface (Figure 9). Here’s the trick: with 12:00 being straight up, assist the weight into position, pointing the weighted end to either 10:00 (if it’s the right elbow) or 2:00 (left elbow), and then start lowering. Follow that angle all the way through the repetition as if the clock face was fixed to the weight and 12:00 stays in line with your forearm. Retest at each angle by bending your elbow and sliding your forearm toward your chest (Figure 10).

If testing fails to elicit pain, you may need to increase the load. If the weight is difficult to lower in a controlled fashion, it is likely too heavy. If you can’t isolate the pain, then you either do not have tendinosis or you have a different version. Tendinosis in the supinator or the distal end of the biceps is less common, but I still see multiple cases every year. If you’re not sure of the diagnosis, see a medical professional.

THE PROGRAM

A muscle lowering a load is roughly 40 percent stronger than one trying to lift a load. For instance, you may be able to lower yourself with one arm in a controlled fashion, but you can’t necessarily do a onearm pull-up. Remember that tendinosis is instigated by a strength differential that we don’t want to propagate. By lowering the weight we are not necessarily pushing the muscle to further strengthen, but we are still forcing the tendon to adapt.

This program will usually take between four and 12 weeks, depending on how much you’ve ignored your elbow pain.

At the angle you isolated during the testing protocol, do three sets of eight repetitions, morning and night, every other day. As mentioned, the weight/resistance should be high. Low-weight programs are notoriously ineffective.

There are many instances where this set/ rep ratio is either slow or too aggravating. That does not mean the program will not work, just that you need to tweak the program. Usually, this involves lowering the reps and increasing the weight. If your elbow is quite irritable, try starting with two sets rather than three.

Take a week’s rest at the four- to six-week mark. Every second week, retest the elbow angle, as the location of pain will tend to become more specific as the amount of tendinosis reduces and the affected area is therefore easier to miss. You can lose a lot of time hammering away at an angle that is not hitting the target.

Soft-tissue work is imperative. The program will produce some muscle spasm and likely ramp up any tendonitis. Ten minutes of eyewatering massage over the tendon and upper forearm a few times a week will double your chances of success. Note that massage alone is categorically ineffective. If healing was as easy as rubbing it, we would have figured out how to cure our sore elbow soon after we discovered masturbation.

There is a small subset of people who, with significant and ongoing pain leading up to initiating the program, respond quickly, often recovering within a couple of weeks. This tends to happen more with lateral epicondylosis than the medial counterpart. Though I’d like to believe there is a Wolverine gene involved, I tend to think there is another pathology at play that presents like tendinosis and responds to eccentric loading. Perhaps it is some kind of fiber deformation at the musculotendonous junction or possible fascial strain (the thin membrane that lies between muscle layers).