Click here to download the pdf

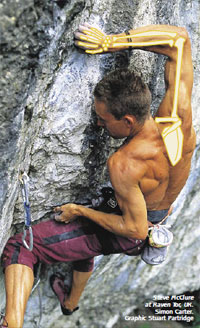

As any biologist will tell you, ‘the Golden Rule’ when studying an organism is that structure governs function. Our shoulders are purportedly designed for everyday dexterity and range of motion, not swinging about on vines— or for that matter, cliffs. Ask a few of your friends; chances are that at some point one of them has injured a shoulder while climbing.

The cause of shoulder pain in more than 80 per cent of cases is commonly known as impingement and usually involves a muscle called the supraspinatus. This is one of four muscles collectively known as the rotator cuff (RC), which both stabilise and facilitate movement of the shoulder.

The bony bit on the tip of your shoulder is actually the top of a bridge, formed by a couple of bones and the odd ligament, and runs from front to back. The tendon of the supraspinatus muscle runs under this bridge. If you injure one of the RC muscles it can disrupt their control of the joint. In many cases this allows the head of the humorous (the bone between your elbow and shoulder) to migrate upward, pushing the tendon of the supraspinatus into the underside of the arch.

Now this is a rather complicated area, prone to misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

Unfortunately for some, impingement won’t get you a shot of morphine at the emergency department, let alone a guest appearance on ‘RPA’.

The fine line between pleasure and pain

With this injury it is just pain, normally quite sharp. If you are experiencing some pleasure I suggest you try the ‘Personals’ column in your local newspaper.

Although the initial injury probably occurred when you pulled like a husky on speed, the pain can be worse when you are doing small movements that feel automatic: reaching and turning a doorknob, doing up your shoelaces and— attention all climbers—reaching above your head. The pain will often cause you to falter halfway through the motion, your arm and shoulder dropping towards the ground. As you lift your arm it tends to pass through a painful zone, the pain decreasing as you raise it higher.

Now what? Good question: the problem being that this is a secondary injury. The primary injury is the one that originally disrupted the motor control of the shoulder. I would like to say that if you just stretch this muscle and that muscle your shoulder will get better; but it probably won’t. The correct response is to see someone about it. There are many things that can cause impingement, from a stiff upper back to tightness in any of the 17 muscles that attach to your shoulderblade. Finding the problem and treating it will be the one thing that will help. If you don’t, you could end up with a few other nasties. Chronic pinching can lead to tendonitis, tendinosis, and tearing of the tendon. This leads to pain, which leads to further disruption of the muscle control and, yes, more impingement. Treatment will often entail stretches, manual therapy and, importantly, some exercises to re-educate the RC and regain normal control of the joint.

Avoidance is better than treatment

If you hurt your shoulder and don’t want to see someone about it, give it a rest until the pain subsides. Your shoulder is a sensitive puppy and pain is a great catalyst for biomechanical mayhem. If you direct your shoulder to do things whilst it is painful, it will change the way it responds. If the injury causing the pain does not retard muscle control, the pain itself will…then you get impingement.

Do this enough and by virtue of reinforcement your brain will only remember the abnormal motor pattern—then you will definitely have a problem.

One of the best things you can do is to keep your upper back and shoulders free of tightness. Be nice to yourself: get a massage every few weeks, stretch regularly, and, if you can, go and do some yoga. Get the instructor to be your handbrake as most climbers can only ex ercise at volume 1000, full throttle, non-stop disco ac tion. I often prescribe gentle stretches to patients. It is alarmingly common for them to return with a different injury because they chose to stretch 937 times a day, only stopping to wipe the sweat from their eyes.

The shoulder is particularly complex; possibly the most complex of the larger joints and one of the most susceptible to damage. Most climbers who train regularly will probably injure one. As a take-home message: try very hard not to get a shoulder injury, you don’t want one. And ‘see your doctor if pain persists’.